Ravages of Time - an in-depth analysis

"Today a young man on acid realized that all matter is merely energy condensed to a slow vibration. That we are all one consciousness experiencing itself subjectively. There is no such thing as death, life is only a dream, and we’re the imagination of ourselves.” -Bill Hicks (to be honest, I am not really familiar with his works)

INTRODUCTION

Things written here will be a mix of what Ravages of Time offers directly, as well as my (on top of the feedback of the people I have been discussing them with) thought-process, interpretations, what I got from consuming it and what I realized meanwhile writing this giant text wall of an analysis, that I want to dedicate to my all-time favourite piece of art - so I won’t be surprised if anyone could find something to disagree with. I will also be giving titles and numbers before starting some paragraphs, while also typing next to them whether they will have spoilers or not - for it to be easy to operate by the ones who have read and who have yet to read Ravage’, alike.

Ravages of Time is almost fully focused around the grand scheme of things - It is about just how farsighted, the ones that make the crucial decisions towards saving the country, can be, compromising to each other and finding common ground with the several other factions, while all of them having the plans that they did not reveal amidst the arrangements with others. Of course, they all will be forced to sacrifice things that are highly important to them or to others, to do so and eat the consequences in one way or another.

Keep up with convoluted combos of schemes that mobilize various things under the sun, featuring decently competent minor players and illuminati level geniuses that make other masterminds look like beginners

Dive down into profound reflections covering many topics and engaging with multiple ideological tendencies and schools of thought, as participants and bystanders muse about their situations alongside the bigger picture

Hang on through incisive instances of social commentary, in which both composer and characters grapple with different issues that resonate and remain relevant, as if obliquely speaking about contemporary affairs

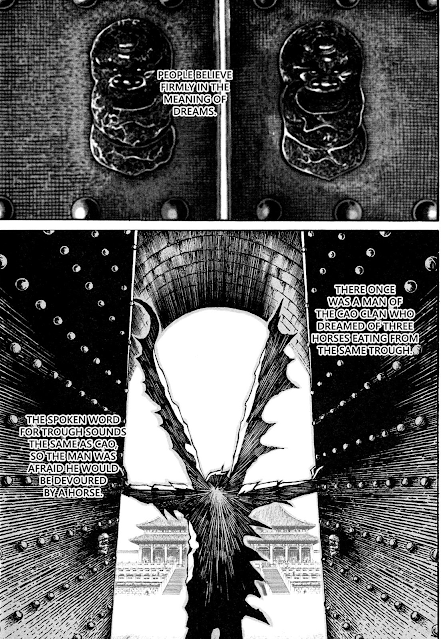

Look out for extensive fancy quotes and idioms from assorted ancient sources, echoed in narrative voices and spoken by witty actors who enjoy playing with words frequently lost in translation

Are the lessons of history one-sided, or do they convey unfathomable depth?

Should one continue to protect the old ways, or shall one propagate by treading new paths?

Does heaven side with benevolence and righteousness, or is it constantly watching in silence?

When things fall apart, must we place more blame on incompetent rulers, or ambitious vassals?

Would it be more heroic to stay loyal and defiant until death and be immortalized for it, or to wisely choose another branch and endure the infamy to survive for a comeback?

Will it be better to set a good example by cultivating virtue and slowly winning hearts and minds, or to expediently take over and quickly impose order by any means to secure future generations?

Will our heroes or opportunists alike be able to make life and death decisions between the loved ones and the world peace?

Are people capable of distinguishing the real and the fake identities of not only so-called saviours, but their own as well?

How are we defined by the false rumors that we spread by ourselves or the lies we tell to oneself and by the legends that were cultivated without our consent?

When chaos arises, on which path does the one get placed as a result of being raised in either poverty or comfort?

From where does one find the source of passion to move forward on each of said paths?

In the world of deception, controlled by selfish and selfless romantics - where on the surface everyone is presented as either god of war, genius or both - who should be let to guide the people?

Can we by any means consider someone who contradicts himself as a liar? Should we really consider contradiction as a flaw, despite the fact that everything we do could be a contradiction?

What are the means of preserving a peaceful order, despite the inherent longing towards chaos in human nature and vice versa?

A win achieved through the hardships that dooms the whole path towards the goal or a loss of a war and a life that accomplishes the goal - who is the actual winner amidst the chaos?

Does this world of clashing ambitions offer anything else than the never-ending struggle of satisfying said ambitions that, in the end, transforms into the longing for relief?

What about the shared knowledge of sages about saving the world that ironically spawns an even fiery phoenix scorching the plains?

Are dreams inherently selfish or selfless? While waiting for a country to prosper, do not you wish for yourself to live a comfortable life? Is not that a basis behind the creation of civilization, to live and let live?

SUBTLETIES

What is the biggest advantage of the Ravages of Time? Well I would say that it is the cryptic and (may be even overly) subtle nature of its narrative. On the surface, it's just a war-drama with a lot pathos, throwing you into warfare for more than 500 chapters, while characters throwing all sorts of flamboyant action for no personal reason at all and throw some sentences to both look and sound smart, that which may or may not hype you up, you may just end up annoyed. But if you decide to dive deeper, you will notice that Ravages have a lot of connected layers and offer you a possibility to discuss a lot of topics from a lot of angles. So it does not matter whether you will like it or not, whether you want to dive deeper or not, the long ride will most likely pay-off to you, in one way or another. I would say that the presentation of the scenes is quite theatrical, on top of that - POV cuts around quite often on the scenes and skips the transitional movement. For example, an assassin stopping in front of a warlord and in the next scene, having that warlord abducted to another place. It is up to interpretation how that happened, but from the available information we for sure know that such a thing to happen was within the possibility. Now some events and action scenes may be off-screened - for example, family stuff at the end of the Guandu arc - but I think skipping them tends to be excused and even the family stuff is justified, considering the author wanted to explored that specific themes later on anyways, so right now giving it more focus would render the future arc redundant, but now, by skipping, the arc was allowed to add another layer to that theme and I will explain that later on. Oh, and there are a lot of time-skips, considering the work is supposed to cover more than 20 years of history - some may think that it would disrupt the flow, but considering the length of the plot, I think time skips happen with enough in-between scenes to fit in and sometimes they may even go unnoticeable, so I would say the job is done quite well.

Taking the actions and movements aside, direct dialogues of the characters may as well be indirect and contain double meaning, talking about several other characters, hidden in a plain sight. The example are quite many, so I will take the ones that will come to mind - when Zhang Fei and Liu Bei are talking about the paintings, the meaning behind that dialogue is, that Liu bei is aware of how Fei was manipulating him and he is asking about that; Guo Jia and Cao Cao talking about Cao Cao’s children, in that one Guo Jia’s words can be applied to several pair of brothers in that arc, be it the geniuses themselves, Cao Cao’s children, the unnamed brother that he commanded to kill and so on; Sima Yi, Pang Tong and Zhao Yun meeting and throwing un-addressed sentences, because these sentences could be applied to all three of them at the same time.

One thing that should be taken into account while talking about the dialogue is the translation - Ravages of Time has a lot of word-plays in each chapter and not only it is too hard to translate, but many sayings are untranslatable and easily get lost in translation. Also, because of the high amount of references, it is also a separate work to determine which one exactly are the sentences that belong to other authors. That may be connected to my only flaw regarding the dialogue writing - one of the sayings, for parallelism purposes or some other reason, are repeated too many times to be subtle.

when it comes to assessing merc's overall translation effort, I suppose one can distinguish 4 cases

I would presume that the parts in Ravages that make use of standard written chinese are translated well enough

when it comes to the parts in Ravages that consist of various idioms and aphorisms, perhaps other chinese speakers might find some of the wording in english awkward (but I can't say much since I'm not fluent anyway)

the parts in Ravages that consist of - passages from ancient texts but which aren't popularized as idioms - present another challenge (and in this case merc for the most port relies on available translations - and whatever awkwardness that ensues can partly be attributed to the other translators - or otherwise tries to translate matters in a readable fashion)

what's particularly tricky are the parts in Ravages - where Chen Mou waxes poetic and loads stuff with wordplay or tries to imitate classical registers without directly quoting some passage (or alternatively, those parts involving - phrases or particles featured in cantonese but not so much in mandarin)

if there's anything english speakers would want to nitpick on, it would be the occasional grammatical errors or stylistic glitches (and I can't be bothered to point them all out and propose adjustments, haha)

ARTWORK

Now when it comes to artwork, it is quite a tricky situation - it offers a lot in terms of photo-realism and most of the time everything feels organic, so it is hard to notice just how narrow it is in certain aspects, that may or may not hinder the experience of the readers. I personally do not even mind its shortcomings as it capitalizes on impact and manages to depict moments memorable and climactic enough to be iconic to me, but would be fair for others to not hold it in high regard.

One thing that the artstyle is prioritizing and incorporating in it, is to draw inspiration from the chinese larger-than-life action cinema - character designs are close to being photo-realistic at some point (with over five hundred distinct faces, including the no-name and background soldiers, with their own distinct attires - that connects well with the realism of said era, as the many were not dressed in uniforms and were supposed to make their own armor) and frequently offers all-new kind of situations that may sometime serve as symbolic imagery that will fit subject matter of characters’ internal thought and won’t be put down-out-throats.

battle choreography is almost always more than mere slashes, people use different sort of weapons, ride horses around while fighting and use both environment and varied number of participants in said fight scenes, so they are not really just mere duels, but the strategies on their own. And in general, body language is suitable and presents the type of characters they are in a subtle manner, with no over-the-top presentation of their personality traits. What makes these fight scenes even better is the momentum, that is not being hindered by the convoluted explanation of power systems and in general, characters are not limited by said power system to alter the course of the history.

Paneling itself won’t really offer anything extraordinary, but it will be just fine to flow smoothly, it won’t start placing you awkward to read perspectives by changing in a bizarre manner and confusing your focus. Environment in itself does not have much depth of field and characters won’t interact with decorations much, because of its more theatrical approach to depiction, so the decoration tends to be drawn in separate panels, which is a simple/cheap but effective way to liven up the flow by swapping the point of view panel-by-panel.

Few flaws that can be found in this department include the repetitiveness - twice or thrice you may notice some panels copy-pasted, ‘skeleton’ of some stances and angles to said stances used as a template, as well as facial expressions are not really unique lately and generally in the second half said expressions are not really expressive (although it fits the tone change and how hardened are the people to express anything), but paneling serves well enough to lie to eyes in the heat of the moment for said flaws to remain mostly unnoticed and not affect the read experience much, but in hindsight I started missing the type of drawing that the first half had.

What makes it worse is the fact that the quality of RAW scans have drastically declined and if you are reading the english scanlation, you may think that the artstyle declined more than it actually did. But surely, it declined in quality and it may be noticed in inconsistency (noticed - because how perfectly consistent the first half is in terms of it - everything looks panel-by-panel to the point that you can take any panel from there and expand as a double page spread, with stand-out pages that resemble classic painting for a bit, with their dynamic usage of body language of several characters), as the backgrounds are not as detailed anymore, sometimes characters on background lack the faces, line-work is also rough, shading is not used as much and it's hard to find good assistants in china good enough assistants as the industry is not really as advanced as the one in Japan. At least the ever changing style highlights the journey of the author to fit his personal growth in the span of 20 years.

PREMISE

I hope no one will mind me citing the premise from someone else’s LotGH analysis (as I do not think I will be able to define the term in a better manner), because of how similar the subject matter of these series is (and I will repeatedly mention that anime for comparison’s sake as well.

Analysis in question -

‘What defines a legend? Well, if we pop open the nearest thesaurus or dictionary, we're certain to get a slew of similar answers. It most commonly refers to a hodgepodge of cultural myths, or extravagant stories of select events, time periods, or people. Though ultimately, a legend is something elusory. While it may be birthed from some stray fact, the subject becomes so fantastic through each reiteration that, after a few rounds of tall tale telephone, something pedestrian may become extraordinary.

But, when this organic evolution is supercharged by direct manipulation and mass hysteria, a legend becomes more than just a story – it becomes a weapon. It goes on to perpetuate the agendas of those who use it; shifting each re-telling away from the truth by varying degrees. And for us, this seems to be an ever more present danger, as our contemporary era is becoming increasingly more defined by the idea that “objectivity is a myth”. And while we, as a global civilization, have created and consumed metric tons of propaganda since the dawn of the written word, it doesn't stop the idea of a legend from being an attractive tool to enact massive change, whether altruistic or apocalyptic.

For example, remember those 300 Spartans, standing stoic and solitary against the millions of invading Persian soldiers, at the Battle of Thermopylae? Yeah… they had a lot of help.

Over 6,000 soldiers combined from 31 Greek Cities were present at Thermopylae, and while the Persian army was absolutely massive (around 300,000 soldiers by the largest estimates), it was hardly equal to the rumors which swirled around immediately following the battle. And the battle itself wasn't some hail-Mary-moment either; it was a stalling action so that the Athenian Navy could defeat the Persian Navy at the Battle of Artemision. If the Persians could just sail on by them, no number of impressive phalanxes would do the Spartans any good. And the Greeks primarily held out because of their specific placement on the battlefield, and that the Persian army hadn't modernized in decades, not just because they were badasses.

And when the Persians did rip the Greeks at Thermopylae apart, with the essential victory at sea secured, this loss didn't sap Greece's morale, but instead galvanized the city-states against the Persian advance. Even though the Athenians were the real brains behind the defense of the peninsula for most of the war, the Spartans are the ones who've consistently gotten the credit within popular culture. And that isn't accidental.

Whether legends are built rapidly, or gradually over ages, they affect humans on political, social, and cultural levels. And when someone is able to directly control the central moral of the story to suit their own ends, the effects are clearly reflected in the zeitgeist. And when you've applied this methodology to, say, an intergalactic culture overwhelmed by proxy wars, corruption, and constant revolution; legends are bound to emerge’

Let me also copy several things from wikipedia, for better understanding.

‘In philosophy, becoming is the possibility of change in a thing that has being, that exists.

In the philosophical study of ontology, the concept of becoming originated in ancient Greece with the philosopher Heraclitus of Ephesus, who in the sixth century BC, said that nothing in this world is constant except change and becoming (i.e., everything is impermanent). This point was made by Heraclitus with the famous quote "No man ever steps in the same river twice." His theory stands in direct contrast to the philosophic idea of being, first argued by Parmenides, a Greek philosopher from the italic Magna Grecia, who believed that the change or "becoming" we perceive with our senses is deceptive, and that there is a pure perfect and eternal being behind nature, which is the ultimate truth of being. This point was made by Parmenides with the famous quote "what is-is". Becoming, along with its antithesis of being, are two of the foundation concepts in ontology. Scholars have generally believed that either Parmenides was responding to Heraclitus, or Heraclitus to Parmenides, though opinion on who was responding to whom changed over the course of the 20th century.’

‘German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche wrote that Heraclitus "will remain eternally right with his assertion that being is an empty fiction". Nietzsche developed the vision of a chaotic world in perpetual change and becoming. The state of becoming does not produce fixed entities, such as being, subject, object, substance, thing. These false concepts are the necessary mistakes which consciousness and language employ in order to interpret the chaos of the state of becoming. The mistake of Greek philosophers was to falsify the testimony of the senses and negate the evidence of the state of becoming. By postulating being as the underlying reality of the world, they constructed a comfortable and reassuring "after-world" where the horror of the process of becoming was forgotten, and the empty abstractions of reason appeared as eternal entities.’

‘Impermanence, also known as the philosophical problem of change, is a philosophical concept addressed in a variety of religions and philosophies. In Eastern philosophy it is best known[by whom?] for its role in the Buddhist three marks of existence. It is also an element of Hinduism. In Western philosophy it is most famously known through its first appearance in Greek philosophy in the writings of Heraclitus and in his doctrine of panta rhei (everything flows). In Western philosophy the concept is also called[by whom?] becoming.’

‘Buddhism and Hinduism share the doctrine of Anicca or Anitya, that is "nothing lasts, everything is in constant state of change"; however, they disagree on the Anatta doctrine, that is whether soul exists or not. Even in the details of their respective impermanence theories, state Frank Hoffman and Deegalle Mahinda, Buddhist and Hindu traditions differ. Change associated with Anicca and associated attachments produces sorrow or Dukkha asserts Buddhism and therefore need to be discarded for liberation (nibbana), while Hinduism asserts that not all change and attachments lead to Dukkha and some change – mental or physical or self-knowledge – leads to happiness and therefore need to be sought for liberation (moksha). The Nicca (permanent) in Buddhism is anatta (non-soul), the Nitya in Hinduism is atman (soul).’

RANDOM GIBBERISH

Life is like a dream. People tend to look at the reality through the subjectively made-up lenses that more or less shapes the universe as a collection of fairy tales, in a sense of literally every single human being having a clouded perspective in one way or another and, to put an emphasis, that does not refer to idealists alone, but also pessimists, so-called realists and every shade of it that may come to mind - no matter how you try to be realistic, you are merely trying. People’s views are created by their own eyes, the information that they merely believe in and are combining them through their imagination. So even if you were to try to see others’ perspectives, it would merely be your own imagination again, no matter how open minded you would try to be, your mind won’t be able to fathom the whole world. Not to say that this is a bad thing or a good thing, just an ‘objectivity’ that even I will contradict and contradict as the write-up goes on. Having a certain fixed relationship to someone and reducing him/her as a certain identity shackles the freedom of expanding the relationship and enriching it with no end. Unfortunate part of such ordeals are, of course, the acceptance of things as they are and finding a comfort zone (“a well’ if I may say) unintentionally, not even thinking about going further simply because you do not considering that the identity of someone else may as well be full of contradictions and still well-constructed, naturally. Everyone has had such moments in their lives when they wanted to talk to someone they either do not know or know for about, so they could not find words, topics, anything to talk to and get even closer, as their view about a certain person is set in a small framework, not perceiving that the person could talk about with him about anything. Say, you get used to socializing on the internet to the point of forgetting that real life interactions exists and they function drastically different when compared to internet, you come back to earth and have hard time accepting it, adapting in it - this is a minuscule of an example, as The Ravages of Time takes such understanding and nails around the grand narrative, in which frameworks of millions of dreamers are about to clash each other to DEATH to SAVE the country, comprehending in the process that the core problem is not the fact that in the world are dreamers with opposite ideas of reshaping the world, but they themselves are the problem for living the life like a dream.

People also like to talk about how everything is irrelevant, how everything is objective, how everything is predetermined - but is this really relevant? We won’t ever be able to predict everything at the same time because taking literally everything into account is impossible for anyone and anything, so this can only mean that TO US nothing is predetermined, so why would anyone care about the predeterminism? Are not our views shaped by our perspective and the consensus of our own narrow circles? Like how old egypt thought that they were the epitome of culture when they were comparing themselves to other cultures that they had their eyes on, while other cultures were shaping their own path of evolution and overridden Egypt’s ‘imagination’ by conquering them by unimaginable (for Egyptians) capabilities for warfare. Their perspective was narrowed only on the level of the cultures they were aware that existed could not have imagined that somebody greater than them was out there in the world.

Comparative method is basically a fundamental type of research in the field of Ethnology. “Ethnology is the branch of anthropology that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology).” In short, understanding the culture by deeply comparing cultures that are similar or not to each other. Point being that it is trying to reconstruct history, using all sorts of records and reports as a source to do so. Ravages of Time is doing something similar - it puts the records, legends, reports, novels, video games and whatnot together and examines just how are they being interpreted through the lenses of someone viewing them from the 21th century, in other words we are comparing the contrasting normalcy of the ancient historic cultures and the modern ones, so as to let as notice how unreliable it is to rely on them, considering how contradictory, paranoiac and supernatural history suddenly becomes. You could hear from people that these ‘200 IQ’ strategies are too unrealistic and characters are not relatable to us, but they fail to connect the dots, that message of this work is to let us know exactly THAT. One of the layers, at least.

By pointing this out, I wanted to highlight several things - life is not a closed room or a single book (for instance, a history), there are always certain details about literally everything that make it impossible for us to have a correct, fully rational judgement, so it is inherently unwise to rely your whole life dedicating to one thing or/and judging by the comparison of things, that severely limits the world-view, the unlimited skies, and your ‘dream’ is just ending up as just another well. Things should not be rationalized to the point of remaining alone, in a sense that things do not exist in a vacuum, like how love and hate, love and hate may not be separate things, on the contrary, they may be complementing each other. If one is doing something specific, it is not necessary for him/her to have one motive, you can get many different things by doing one thing.

Now sure, it was probably always meant to be centered around the Three Kingdom era, but there is also another way to look at setting - from a perspective of RoT being a commentary on general history and not being exclusively addressed towards this concrete period. The period, which is the bloodiest and the most chaotic civil war in the history of mankind, so much that it rivals the World War with its death count. Everyone and everything is full of corruption and there are as many misinterpreted stories (intentionally or not), regarding themselves and things that they observe, as many the population is. The world has never been harder for idealists to fix it - would there really be any other era that would perfectly illustrate, through the subtle ‘allegorical’ environment, the unreliability of information and how said information shapes the world.

THE RAVAGED WORLD

Intel is crucial. So-called geniuses here are not the type of smart characters that make some unrealistic strategies out of thin air, without really revealing how they come up with said conclusions, and completely benefit from it with a smug smile and no real loss, while spouting some philosophical monologues. Geniuses here know the world that they inhabit, know each other and the world is also getting familiar with them, the chaotic world with their own agendas and ideals and personal feuds, so coming out clean from the ordeals have never been on the menu, the tides and the sides are both perpetually changing and despite the smug faces that are supposed to serve as a distraction, everyone is trying to improvise, adapt and overcome them, most of the time compromising and changing the priorities according to the consequences of ever-eventful plot-line. Do not get me wrong, the world of Ravages is not so robotic to be so robotic at calculations - characters do have personal grudges here and do not solely rely on ideologies, there are also several conveniences that even the serie itself admits to and people are fail to grasp the nature of some others, thus paying the price by getting backstabbed and etc.

Henceforth we have a clear and an ironic contrast - the world is as chaotic as ever and the characters are all as smart and calculating as it gets. This contrast in itself has several layers to it. One, both of them result in an unreliability of information - if there is a chaos and that breed overly pragmatic warlords, then, intentionally or unintentionally, the correct information won’t be able to be spread, as it could be misinterpreted or completely made up or completely concealed and lost from everyone. Second, one breeds another, order comes when people are fed up with the chaos as it endangers the lives of people that said people cherish, Chaos come from people trying to act smart and thus their different views and agendas of order overlapping with one another, just like the topic about how hard times create the hard people, then said hard people create the soft times, that on its own create soft people, that then result in weak time, that which are responsible for hard times. We can get this contrast by comparing the world of Ravages to our present world, but then there is a layer of people not being able to break out from the identity that they have manufactured on their own to be viewed as something they really are not - take Lu Bu of Ravages, he is way smarter than his counterparts from other sources and that is not merely for an edgy show of ‘man with such a reputation could not have been dumb’, but it also shows that no matter how smart he may have been, there still are a lot of people smarter than him even in Ravages, which still makes him dumber in comparison, so he can’t really escape the meaninglessness of people’s struggles (no matter how great they think they are) when they are confronted with the inevitability of history.

"can one recite poems and read books without knowing who the author is as a person"

The power of the word is immense, it is a fundamental part of communication, which is a fundament of connection in itself. But the humans are deceptive by nature, so can we really believe in words? What happens if it's revealed that everything you have ever known is just subjective, made up by someone else to be perceived as objective? What can we believe in, if everyone lies and both everyone and everything could have been fabricated and weaponized by everyone else? Chaos.

Three Kingdoms era reeks of chaos and thus serves as a perfectly fitting period to portray the paranoia of mankind. What's so great and scary about the available information is the fact that it is accessible to everyone and everyone also encourages the brainwash for it to be perceived as truth. The access, of course, is given by the people from above, by those who were chosen by people - for people - but who knows what they really think about? They have their own sources and they absorb everything, while asserting them as they please, from their perspective. The problem? The fact that there are a limitless number of 'factions' in our world, all of them getting the information, but spread in a different manner.

For instance, take all of the critics - none of them have identical scores, to say the least. And all of them have their own made up rules that by which they declare their judgment as objective, of course blindly believing in it and deem it necessary for the pieces of fictions to meet their own requirements, or else they are failures: "B-but I could not relate to the people from the second century, basically completely opposite environment of mine, it is poorly written, how can I hold my interest". Of course I can compare critics to the ones above all, they tend to sit on their high horses, after all.

Now what Japanese stories forget, while having a high emphasis on individuals and sometimes to their psychology (even while trying to explore philosophy), is, the fact that individuals and their internal conflicts are not supposed to convey the exploration of grander ideas. That type of story-telling on its own shapes the view as if that's the way of how every animanga should be written and philosophical stories get judged by such narrow-minded views. They think that characters themselves should individually bring ideas and represent them, as if they only view character as plot devices/narrative tools, when in reality it is the other way around - it is the narrating world that is supposed to represent all of these ideas and force all of the characters to carry all of these ideas. For instance, how every single side in RoT uses "greater good", in some cases its just an excuse, in some cases it is hypocritical, in some cases they actually practice it and in some cases the whole concept of it is being questioned, in empathetic or apathetic manners.

Power of the word may be immense, but it is not omnipotent. You may spread one gospel, but someone will spread another. You mat spread propaganda, but someone else will spread propaganda about you. Warlords view Art of War in one way and achieve greatness that which will be spread around in different words, that will be re-defined and re-told as the time goes. Then won't we view said warlords in another way, further complicated by the fact that our culture is drastically different from theirs', so the saying from back then will most definitely had something else in mind when compared to our own interpretation.

and that's, ladies and gentlemen, The Ravages of Time - as the black texts at the end of chapters and characters talking about future suggests, it is not only a collection of historical records by a single person, but it also incorporates legends, video games, novels, conspiracy theories, modern ethnology and basically presents what kind of story would we have if we collected any kind of interpretation of said events from the second-third century of China to serve as a socio-political commentary on not only the Three Kingdoms era, but the past in general.

Now of course in Ravages these smug characters are also citing some philosophical stuff, but difference is what these sayings are reinforcing into the narrative. The first and foremost, they are pointing out the idea that the spreading of information is how random talents may arise onto the battlefield (although won't be as farsighted as the one that were trained by the actual masters) and scorch the plains of the country even more, so whenever characters are being introduced, it is not really required to give them some flashbacks for it to make sense - just why do they stand out? Simply because they do not really stand out. And if you dig deeper, a message that could be derived from is, that openly, and not to specific people you are nurturing and can directly observe the influence, giving the whole country the philosophical life-lessons that are supposed to enlighten them in idea, actually does the opposite, as they do not really know the author - should you be really citing the text, while not knowing the author? On its own the characters are also asserting their own understandings to the texts that they have cherry picked. Meaning, that the ones that usually cite are the people who are using these words with their own interpretation and understanding, attaching their own context to them, so, for example, one philosophical sentence may influence two people in different manner and put them on the drastically different paths of their lives, according to their own observation, without anyone to blame. I myself usually see in real life how people cite the cool stuff some CHARACTERS said, while attaching the name of the author next to it, as if the authors agree to every single word their characters say. Ravages of Time goes even beyond that and showcases how this very concept could be weaponized, as someone may purposely release either an unknowingly to masses dumbed-down version of military teachings to counter the ones that learned from them with their original military ways - or straight up write a propaganda to hinder the reputation of someone else, just after you baited out their corruption, for the fiction (propaganda piece) to become a reality.

THE HISTORY IS WRITTEN BY THE WINNERS

… or is it?

Many longtime readers of The Ravages of Time would tend to remember the ‘morale theory’, but also buried in the earlier chapters (but oft-forgotten) is a parallel ‘myth-making theory’.

This lecture will discuss the two theories, how they are dialectically related (despite the apparent divergences), and the insights that both offer regarding warfare and statecraft.

The theory of morale (attributed in-universe to Sima Hui, first articulated by Wen Chou in chapter 31) states: “There are three ways to boost yourself and diminish your enemy. If the enemy commander wins the first encounter, blame your own commander for being reckless; if the enemy commander wins often, blame your own tacticians for poor use of terrain or weather; or if the enemy commander always wins, dismiss them as brave yet brainless.”

Meanwhile, the theory of rumors (articulated by Li Deng in chapter 7) states: “The commanding officers take the credit for a battle of hundreds. After the thousandth retelling, the credit will all go to one man.”

ow it would seem at first glance that the two theories convey opposite messages, in that whereas the first assumes that there are outstanding ‘heroes’ (and that to maintain morale they must be downplayed and explained away), the second assumes that ‘hero tales’ are mere fabrications (to motivate allies or intimidate enemies). Now in order to better see how they are connected, it is important to note that each theory can be interpreted in at least two ways.

For the theory of morale, the practical (and more superficial) reading is to see it as a technique to manage morale by undermining the enemy image and not making it look like one is up against a peerless talent. However, the recursive (and sneakier) reading is to see it as a warning sign in case someone happens to have a suspiciously downplayed reputation.

For the theory of rumors, the simple reading is to see it as a guide to psychological warfare by means of weaving tall tales. The more profound reading is to see it as a comment on disproportionate individual recognition built on the inequitable appropriation of collective labor, and a warning sign in case much of the credit and glory is attributed to a lone figure.

Interestingly enough, the alternate readings of the two theories can be integrated as follows: Renowned leaders tend to benefit from (and symbolize in simplified narratives) the heroic work of their colleagues and subordinates, and in turn the illusion allows the talents below to continue operating effectively (either they remain unrecognized and underestimated at their enemies’ peril, or they are seen as lesser lights enhancing the prestige of the main figure). Combined, they present a nuanced account of how warfare involves an underlying element of real collaborative effort (out of which certain heroes and geniuses emerge and distinguish themselves by various means, if they are lucky) as well as a theatrical (and rhetorical, and ideological) component calibrated for morale management and psychological operations.

Ravages has a few other things to say about rumors and morale that would further highlight the entanglement of these two aspects.

The three-step consolation mechanism seems to be the more iconic portion of the discourse, but the more basic claim of the morale theory (also articulated by Wen Chou in chapter 31) goes as follows: The three-step consolation mechanism seems to be the more iconic portion of the discourse, but the more basic claim of the morale theory (also articulated by Wen Chou in chapter 31) goes as follows: “Officers may be brave, but soldiers do the real fighting. Wars are fought on the morale of soldiers.”

Meanwhile, a poignant remark about the utility of rumors not directly connected to the earlier insight (first articulated by Sima Yi in chapter 74) goes as follows: Meanwhile, a poignant remark about the utility of rumors not directly connected to the earlier insight (first articulated by Sima Yi in chapter 74) goes as follows: “Rumor is the most effective weapon before the start of a war.”

At the core of this is a fascinating contradiction, in that on the hand it is the masses (not the schemers, not the rulers) who ultimately power and enable the collective enterprises we call warfare and statecraft (and more generally, the arenas of political struggle and social order), but on the other hand the masses tend to not be in full control of the process and often end up managed and manipulated and exploited (by the schemers and the rulers) to keep the machinery of domination going and tilt the outcomes of the conflicts.

Thus we see that while morale (and the passion and labor of the moralized and energized) is a testament to people power, rumors (and the discourses and ideological props derived from them) function as control tactics and the means of governance. And yet the propagation of rumors still depends on the morale of people who spread and receive them, and therein lies the possibility for emancipation (or at least, mass defections from one hegemonic narrative to another, preventing winners of one round from forever foreclosing the histories of struggle).

On a side note, it must be emphasized that the demarcation between the rulers (who wield the rumors) and the ruled (whose morale needs to be constantly managed) is not absolute, for even advisers (who are supposed to be above the fray and are trained to calmly assess enemy forces, unlike the rank and file who have to be assuaged by heroic tales and the morale theory) are also swayed by the morale game (since the prospect of entering the prestigious world of the eight geniuses also functions as a motivator for them to keep scheming).

Warfare may be hellish and statecraft may be slavish, but somehow people can be swayed into thinking and laboring as if warfare is heavenly and statecraft is liberating. The elaborate scheming game in Ravages is very much rooted on this more fundamental confidence trick (aptly expressed and exposed by Sun Ce’s discourse on loyalty as method in chapter 174).

note that in all fairness one doesn't have to refer to Ravages just to discuss issues about history and politics, but such an exercise would prove helpful in two ways (for the intellectually-inclined, this shows how Ravages resonates with and echoes certain notions and questions and theories, while for those already reading Ravages this shows what sorts of intellectual openings Ravages presents or suggests for further reflection)

now, many who read Ravages would remember how the series talks about history as propaganda by the winners (and the series (not to mention the composer himself) has a habit of saying this in crude ways), but it's important to note that this is just the surface aspect of how Ravages deals with its roots (and the ways we deal with our complicated lineages)

hopefully the following discussion would help readers be more attuned to the various ideas teased throughout the series (and perhaps, learn by example how one can approach Ravages as a treasury of topics and a site of interrogation)

perhaps the very first instance of historical reflection in the series (not particularly profound, but it paves the way for the rest) appears in the floating narrative text at the end of the dream scene in chapter 1, where speculations abound about how the grand tutor Sima died

note that Sima Yi doesn't die this way in either the historical accounts or the novel but who knows if there's a folk adaptation somewhere talking about Sima Yi meeting a violent end

interestingly, this bit of discussion connects well with the very first black text in the series (our journeys pass into death at some point, but we never really know how we end up in that stage)

the soldiers end up agreeing about the omen (the fire in the shape of the phoenix) but not the actual cause of death also says something about how we tend to overlay/underwrite lives and deaths with symbolism (and narrative)

Ravages as readers know also re-characterizes figures in 3K lore (with some getting more attention than others), and while this is already at play since chapter 1 (starting with Sima Yi being old enough to scheme during Dong Zhuo's takeover of Luoyang), perhaps the first explicit reflection about how people in a given period are perceived by later generations can be found in the black text of chapter 5 (note also the quirky portrayal of Liu Bei early on, even Dong Zhuo still fit the typical depictions (minus him being fat) in his first appearances prior to chapter 8)

“Many years later, there were all kinds of criticism levied against this man named ‘Liu Bei’. They said he stole major cities of Xuzhou and Jingzhou to use as his military base. But the strange thing is… People of all social status in those cities appreciated him and had no complaint about what he did. Was he a bandit? Or a king? Only the future generations have a say in the matter…”

on a side note, among 3K fans, those who like Liu Bei's portrayal in the novel emphasize his idealism, those who like Liu Bei's portrayal in the historical accounts emphasize his charisma and status as a cunning political survivor, and those who dislike Liu Bei deride him as a glorified bandit turned pretender

one other thing the black text suggests is that at the end of the day (regardless of how winners of ages past spin their tales) it is the subsequent generations who come up with their own assessments (and engage in their own struggles for hegemony)

this line of thinking is echoed in chapter 71, as Lu Bu makes his point that people in a given historical juncture (with their own sets of values and principles, interests and desires) don't get to control how they will be perceived by others in the future, though they can try to leave good impressions with their deeds (and stories)

in a way, this illustrates how winners (of a given contest) are never really able to permanently spin things their way (since they die too and loyalty to a given story is not guaranteed)

amusingly, in that instance, even as Lu Bu is gloating about how his treacherous scheme to take over (not necessarily to usurp the emperor, just to be the next hegemon 'under Han') is going well, he's also teasing how as part of the plan he will also play up the image of a hero overthrowing a tyrant and going on to rule with benevolence (which is what many historical accounts try to spin at least in the founding moments of a new regime before the scandals emerge)

now one issue that arises from a simplistic reading of the 'history is written by the winners' slogan is that it seems to assume that people (except the manipulators and the enlightened few) are dupes, but in Ravages the commoners (and the audience) aren't treated as if they were idiots, as we can see in many snippets of commoner discussion

the tension then is that on the one hand those who spin tales do so to manipulate the masses, but on the other hand it's not as if people never notice the games of manipulation that are being played (only that some don't care as much since they're preoccupied with survival or are too disempowered to change things)

it's important to stress that ultimately it is the people with their real longings (even if they haven't examined the emergence of their desires) and real awareness of what affects them (even if they aren't cognizant of the bigger picture and the many tiny details) who end up accepting or acquiescing to the stories, rumors, accounts that they receive (and in turn, circulate and reproduce and appropriate)

and yet, while there are certain things that propagandists and spin doctors can never quite control, there are also certain things that remain at their disposal

even if it were the case that people love the benevolent (or those who serve the people) and hate the corrupt (or those who oppress the people) as a matter of course, the manipulation happens in the filling of the blanks with regard to who gets recognized for what (especially in the context of past accounts that are harder to corroborate by virtue of distance), or which deeds count as righteous and virtuous

having belabored the point about how historical transmission depends upon the very peoples that are supposed to be manipulated in order for the winners to keep perpetuating their spin (and they are not really able to do so completely), I suppose the next issue would be, how are they able to at least manipulate some of the people some of the time long enough for certain stories to take lives of their own and outlast their proponents

this is where an appreciation of the broader circumstances and situations (and systems) that condition what people accept or put up with would come in... certain audiences 'fall for' certain tales, even the most jaded observers (who suspect many things) nonetheless 'go along with' particular accounts (and thus be complicit in their perpetuation) due to various factors, and a big part of it would be that many are in positions where they can hardly afford to openly defy or critically examine

note the remark ‘people are most gullible at a time’ like this which suggests that the quality of alleged gullibility (for who knows what people are really thinking so long as they don't rock the boat) is contingent upon a certain season (and in the context of chapter 147, that's why Liu Bei is being marked as a target because his influence could potentially rock the boat and undermine the narrative for Yuan Shu's breakaway regime)

anyway, those who still bother to follow may be wondering why I meandered about the topic of 'the people' when I planned to discuss 'history' (to be clear, this is just a warmup and a prologue to the discussions to follow)

for one thing, certain theories and approaches regarding the historical experience emphasize a more bottom-up and structural view of things (and although Ravages doesn't go out of its way to prioritize it, this aspect still shows up amidst the subversive heroic tales)

more importantly, this is a demo of what it means to read Ravages from the margins, to treat the text like the scripture puzzle (I mean, one could have discussed people's history as a counterpoint to 'great man' narratives without recourse to Ravages in a separate topic, but instead I tried to showcase how snippets in Ravages suggest this direction, haha)

to recap a bit, it would be very simplistic to say that all Ravages has to say is that winners write history (and if I may add, even taking that conventional edgy line can be treacherous when it comes to historical understanding because many who use that excuse seek not to understand better but to enshrine their own revisions as the new winning stories)

instead, it's important to note that even as the 'victors' (of a given round, and they can lose in the next) try to propagate their narratives and control the discourse, there always already persist undercurrents of resistance among people having their own views and circulating things their own way

note that even though in chapter 509 it's discussed that Zhuge Liang had been manufacturing the heroic tales of Liu Bei for years, none of that would have benefited Liu Bei if the people themselves did not entertain them (or alternatively, if the people weren't entertained and captivated enough by them)

this complication of course goes to show that notions of collective memory and people's history are not so much silver linings that somehow recover the perfect truth (and silver bullets that destroy the lies of the official accounts), but rather that they represent real limits to the extent in which winners get to have their say

especially considering that Shu didn't manage to restore Han and thus lost out in the power struggle, various factors (whether it's elite interests of subsequent periods to derive legitimacy from Liu Bei's example, or simply the popularity of the stories) contributed to the perpetuation of the view favoring Liu Bei, culminating in the Romance

o explore these complex dynamics further, consider for instance Wen Ping's claim that the 'heroic tales' have 'taken root' (even to the point that Liu Biao, the former governor of Jingzhou, believed in them and thus welcomed Liu Bei to the province)

this doesn't necessarily mean that the people accepted every single sentence and each bit of detail, but that they welcomed the stories (perhaps since the stories resonated with them just like how we attend to stories to this day) and would go on to transmit them (and more importantly, to 'continue' the lore in different ways)

the idea suggested in the page is that various players (with their own agenda and commitments) may try to propagate and memorialize various discourses (with the aid of ideological apparatuses and communications media), but to achieve some sort of success they also have to manipulate and negotiate with diverse populations in order for the discourses to take root (and part of it may be to craft stories that engage their audiences)

I had to stress the limits of (and resistances to) the smugly articulated angle of victors' history early on (before moving on to assorted musings on the historical experience) so that readers would be encouraged to read Ravages more attentively, taking careful note of the other nuances and niceties woven into the text (without a shallow sense of cynical elitism)

to put it briefly, just like the morale theory (and history in general), there are superficial lessons and profound insights to learn

it is said that winners (absolutely) get to write history but the irony is that history writes no (absolute) winners

YOU CHEAT, I SWINDLE… WHO KNOWS WHAT WE ARE REALLY THINKING

texts conceal, interpretations mislead, who knows what composers and readers are really thinking

this is perhaps an apt way to describe the predicament we find ourselves in as we come to terms with the precious relics handed down to us, the lost fragments we stumble upon (and the ruins we leave behind along the way)

it's not simply that the records have their spin or readers have their bias (and all we have to do is expose and isolate them, then we get to the unvarnished truth), it's that the layers and networks of partial meaning ensnare seekers and investigators into a labyrinth full of twists and turns and missing links and dead-ends... and yet amidst the disavowals and doubts and suspicions there is at least an affirmation of something, namely that history-making amidst the ravages of time involves making sense of old traces and making new threads out of them (just as Ravages is grappling with 3K lore and coming up with new interventions about it)

and perhaps, bracketing for a moment the many jaded and somber (or edgy and pretentious) voices echoed in Ravages and channeled by readers like myself, there's at least this humble plea articulated by the floating text on the lower left section of this page in chapter 192: “Truth exists. But the truth of this land will forever exist in a gray area”.

"winner takes all'' falls apart even when you just ask for the definition of "win" and the "winner". So let's take the Guandu, that quite literally subverts the term

what did you win - is important, because of not only what you lost (a lot of soldiers that LOST, from your side and, well, you were supposed to fight for them) but what you gained, because corrupted traits of someone you opposed could have transferred on you (see, Yang). On the surface, you won the meaningless land, but deep down ruined the future of your own. You really took ALL.

how did you win - well, take Zhuge Liang, but I will save him for later topics. Shortly - in the Four Commanderies arc, Zhuge did not just write the villains off as "Yuan Shu".... he first forced actions out of them and proved their corrupted nature and only after then he started to radicalize their corruption... of course he was also gradually implementing the propaganda amidst the chaos

what did that win result in - is important, because if your win did not cause the fundamental change, someone will come and undo your doings by your own acquired and established influence (like how Reinhard (from LotGH) came in power - he did not cause fundamental changes, so anyone who comes after him will have enough influence to establish "my son takes all" all over again)

Winner - well, why are YOU the winner, if you were fighting for people and now the world is in chaos, thus the loss for the masses.

What about Yuan Fang, who wanted to ruin the Yuan clan and achieved it? Wasn't he who took it all? What about that one soldier who had nothing to fight for? Did he not achieve relief?

So, yeah, the winner is definitely right... for a short amount of time... and only in his delusion. His own version of history will only raise some contradictions

now hopefully with a better appreciation of the broad strokes in how Ravages approaches the topic of 'history' and its many questions and issues (that it's not all about winners making stuff up, but more about histories of struggle, from competing factions struggling for hegemony, to competing threads of meaning and ways of accounting for the past) we can then proceed to explore the various elements and portions in more detail

if chapter 5 features the first detailed attempt at re-characterizing notable 3K figures (note that chapters 1-4 and 6 are mostly original subplots that establish the initial main faction, while chapter 5 is based on an episode in Romance and thus has more room to play around with established personalities), then chapter 7 features the first sustained reflection (and a rather playful one) about one aspect of history-making and remembrance, namely the recognition of 'heroes'

in all fairness, by dismissing the feat of the 'one-eyed assassin' (singlehandedly killing a notable adviser guarded by 15 elites) as an incredulous 'fabrication', Liu Zong is simply being prudent and circumspect as an outside listener given the absence of clear evidence about the event (note further that some time after the events in chapter 4 Xu Chu kills the surviving witness in a fit of rage), not to mention its prima facie implausibility (though even this judgment call also relies on many assumptions about how things work)

it also goes without saying that much of historical analysis and criticism also consists of such disavowals (and reinterpretations) of certain alleged occurrences, and many ancient historians and theorists of history have engaged in this

what's more significant is that Liu Zong didn't simply discard the rumor as idle talk (not worth mentioning in serious discussion) and left it at that, but that he attempted to explain its emergence and circulation (and by extension, he attempted to come up with a (mostly psychologistic and instrumentalist) theory about the origin and function of 'myths' and 'legends')

that is to say, in the context of the conflict he takes part of, he reframes the rumor as a tactic to boost allied morale and to dampen enemy morale (and assumes it to be an appropriate counter to another seemingly unsubstantiated rumor about the 'god of war' Lu Bu)

this explanation also serves to clarify (from Liu Zong's standpoint) why 'heroic legends' tend to be presented in dramatized and hyped-up fashion with various sorts of narrative gimmicks (as these characteristics are said to help in morale management)

note for instance how the Guandong alliance understands the tale of the one-eyed assassin (or rather, how the rumors are spread in the alliance): supposedly the Sima clan (conveniently the one clan who snubbed Dong Zhuo's invitation and nominally on good terms with the alliance) sent the assassin to take out one of Dong Zhuo's most important advisers (and the one reputed to be among the 'wisest' which could itself be very well a cultivated rumor)

by combining these factors it makes it seem as if the one-eyed assassin is on their side (thus morale is boosted) and writers including compilers of historical accounts do this all the time, make various sorts of associations to generate particular orientations of meaning

if the rumor was just that the Sima clan sent assassins to waylay Xu Lin, it wouldn't be as exciting, and if the rumor was just that some random assassin took out Xu Lin, the alliance could very well have been scared out of its wits (since who knows if the killer would also target Yuan Shao)

if Liu Zong's point stresses the utility of rumors and legends as the swords and shields of psychological warfare (especially if the power struggle is stuck in a stalemate), then Li Deng's brief contribution provides a sharper interrogation of how 'heroic legends' come about

it's not simply that rumors exaggerate for the sake of morale (that is to say, that the 'facts' are simply 'enhanced'), but that the rumors effectively conceal and marginalize something else (in this case, collective action is eclipsed by deeds of 'great men' or more generally, people's history is swept aside in favor of elite history)

I like it when minor characters are used to articulate profound insights, haha

note that the claim isn't that there are absolutely no notably talented people who are recognized and rise to prominence (there may very well be lots of them, but they work and shine in teams), rather it's a recognition that many of the so-called outstanding figures at best function as mere metonymic stand-ins and mnemonic representations for the collective pool of talent that allowed them to rise, and at worst unjustly soak up all the glory while those who have aided them are reduced to background tools

but what makes chapter 7 playful (and thus more complex than just a sermon on the exaggerations of heroic tales) can be seen in what Liu Zong does next (and culminating in Lu Bu's heroic feat, complimented by the black text showcasing a tale of two heroes)

so after Liu Zong delivers his lesson on rumors and heroic tales as methods of warfare, he then attempts to take the credit for the rumor (and in so doing he tries to create his own heroic legend while sidelining the other rumormongers as the mastermind who was able to counter one rumor with another)

and since he already took time to explain his views, by the time he 'reveals' the secret history (who knows if Liu Zong really talked to Yuan Shao about weaponizing the rumor, all we can see is that Liu Zong is weaponizing this rumor about himself weaponizing the rumor about the one-eyed assassin, to boost the morale of his subordinates and make himself look like a cunning schemer which is in and of itself a cunning scheme) the soldiers find it believable and would thus be inclined to spread the meta-rumor (and even as late as chapter 17 people still believed in Liu Zong's spin long after his death)

therein lies the twist: 'heroic legends' (regardless of how true or accurate they are) appear to be painted targets for interrogation and criticism from various angles, but what's trickier and more treacherous (and thus more deserving of scrutiny) are the seemingly reasonable explanations and stories (that in turn conceal their own biases and agenda)

we see this in how Yuan Fang tricked the Guandong alliance in the Hulao pass mini-arc, and we see this in the convincing fictionalizations that occur in historical texts (for example, when so-and-so is said to have quoted something, can we really ascertain they said it? and yet we take those for granted)

it's important to take these complications in mind because such layers can also be found in historical accounts (and retellings of historical accounts, and commentaries on historical accounts)

I don't call some stories propaganda for nothing, haha. read simplistically, Ravages will look like (pro-Lu Bu) propaganda to dismiss historical investigation too

before proceeding to the next phase, I should note a few more things

Liu Zong has fair enough reason to cast doubt on the rumor of the one-eyed assassin (and the rumor of Lu Bu singlehandedly taking out one-eyed generals), but that's also partly due to how the stories have been simplified upon circulation (not to mention that some details such as Liaoyuan Huo not being one-eyed and infiltrating the Zhao clan to get close to Xu Lin are left hidden from those who aren't part of the conspiracy)

in addition, Lu Bu's raid in chapter 7 (along with Zhang Liao's elaboration of it in chapter 31) would serve as a reminder that sometimes, certain people get to do certain amazing feats, but that their execution may very well be due to a combination of factors (perhaps Liu Zong's camp was simply too lax, perhaps there was the sky was really dark that night) some of which aren't accounted for or remain unrecognized in the retellings (depending on the agenda and biases of those who report the story)

people forget this when they start reading historical events as primarily about amazing biographies

and thus in line with the morale theory and the theory of rumors, the clever commando mission of targeting certain generals and tricking enemy soldiers into fighting one another at night gets garbled into a story of how a brave but reckless commander lost many soldiers just to take out one general

much of Ravages has been about speculative and conjectural extrapolation of and commentary on bygone events (using certain (at times anachronistic) assumptions and conventions to elicit certain portrayals)

some think Ravages is just dealing with certain discrete and quirky what-ifs (change the portrayal of this episode, alter the characterization of that figure) and to be fair it does engage in a lot of that, but upon closer and more systematic inspection one can say that more than just doing counterfactuals, Ravages is also invested in simulating how alterations and complications in the currently accepted trajectory can nonetheless replicate similar results (thus the consistent approach of adding convoluted rounds and layers of scheming)

now, the discursive threads articulated by the likes of Liu Zong and Li Deng did not disappear with their deaths

for instance, in chapter 65 Liaoyuan Huo comes to a realization that those who acquire reputations of 'invincibility' could not simply have brute forced their way into fame (either the simplified rumor is a spiked compliment that serves as a coping device in line with the morale theory, or it is propaganda meant to conceal the hidden schemes and structural factors that enabled the dominance... in any case the general lesson is that there's more to the rumors than what's being alleged)

and then there's this reflection in chapter 136 about how renown is very much a social function (that depends on media machinery on the one hand, and popular recognition on the other hand)

going back to Li Deng's point about how collective efforts end up recast as individual deeds, perhaps the way it works is that some people happen to have established status or social position (like when generals take the credit for what their soldiers have accomplished or when entrepreneurs are glorified for exploiting labor and making a profit), or perhaps some happen to be more charismatic and outspoken and thus end up becoming the face of a group, or it could be that some end up making rumors about themselves and thus took the opportunity to become famous (like what Liu Zong did)

the point being that one doesn't just become famous for doing something, there are conditions and competing opportunities to get noticed and 'earn a place in history' (and thus acknowledging this also means conceding that attempts at historical remembrance are partial even if not partisan)

of course, we also have to acknowledge that rumors and heroic legends just like memes can outlive their original contexts and bloom in new situations, that even if certain rumors were concocted and proliferated as part of some tactic, they can continue to spread (in garbled and altered forms) far and wide beyond the circumstances that spawned them, depending on how others receive and communicate said rumors

this reiterates once more that there remain alternate channels that resist attempts by elites and 'winners' to fully control the narrative and perfectly rewrite things as it suits them which is not to say that the rumors are always true, but that a monopoly on allegations and credibility is prevented (thus when rumors become inconvenient, authorities try to suppress them, either by information embargos or by coming up with counter rumors and official rebuttals)

notable in this scene is how the tale of the Handicapped Warriors has pretty much lost its mystique and power (among officers in the south, years after the heyday of the assassin group which was based in the north and center) whereas previously stories about the one-eyed assassin (and the Handicapped Warriors as a whole) were spread to strike fear into the hearts of many... and yet the rumor persists, even without the reverence (and almost as a joke), and so the story lives for another day whether or not it is included in official accounts

a reminder that oral histories are very important sources of information (if not necessarily about past events, then at least how those events have been handed down and appreciated) especially for certain communities that do not keep lasting records

and then there's the reminder that even if rumors can be garbled, the assumptions we use to accept or reject them also need to be examined (note how the officers are assuming that if so and so rumors of heroic feats are true, then the hero should have been promoted long ago or should have moved on to greener pastures without even bothering to investigate the circumstances behind the feats or the reasons for the deliberate concealment)

there are no pure sources to rely on, and thus there is no shortcut to careful examination and study (which incidentally is what the intelligence networks of various factions presumably do, to filter out deception and come up with better counter deceptions and it is also this disinfo game that partly makes historical accounts tricky)

so far we've looked into rumors and legends and folktales as one alternative pathway of historical representation (and how Ravages explores them from different angles and what insights we can derive from the text even if these not explicitly stated in argumentative fashion)

while it has been emphasized that rumors can be inaccurate or exaggerated, the other side of the story is that despite these problematic characteristics the rumors are but attempts to speak about things that have made their mark (or alternatively, even if certain rumors are mostly fabricated, the very acts of fabrication are themselves interventions that make their mark like when we say that certain stories are historically significant regardless of whether they're purporting to represent true events)

replace 'rumor' and 'story' with 'sagely words' (theoretical musings, philosophical reflections, ideological proclamations, etc.) and the observation still holds for the most part

sagely words were spoken, but history was written

beyond the literal contrast between what sages say and what is written in history (a curious setup because Ravages also goes out of its way to interrogate the reliability of historical accounts), this can also be taken to mean a figurative contrast between mere opinionated utterances and the deeds that make their impact (and are memorialized) given the context that Liu Bei is telling Zhang Liao to forego the sagely advice on loyalty and choose to survive to carve his own path (so that Liu Bei can carve his own as well by taking credit for Zhang Liao's submission to Cao Cao)

but another way to look at it would be that a distinction is being made between 'what is said' (looking at history primarily as representation and interpretation and discourse, focusing on documented/stated allegations and their truth and meaning) and 'what is written' (looking at history mainly in terms of effects and traces, focusing on forces and trajectories regardless of the accuracy of the reports, in fact seeing reports themselves as symptoms and consequences)

with this in mind, we can view 'heroes' in another light, namely as historical agents who make their mark (who are not content to simply be written about in historical accounts or rumors, but who act in ways that help make or shape the historical trend)

like when we speak about 'history in the making' or 'moments that make history' (not in the sense of someone writing about something, but of doing deeds that get written about)

let us revisit for instance the story of the one-eyed assassin and Lu Bu's feat of taking out one-eyed generals, to clarify the distinction between the two ways of approaching history

under the first representational mode, someone does something, which gets talked and written about in different ways, and we focus on assessing the accuracy or fairness of the attributions and allegations (did the assassin do it by himself, how could he have killed 15 elite bodyguards, what allowed Lu Bu to sneak into a well-guarded camp, did Xu Lin really say what he supposedly said, are the rumors true, etc.)

under the second symptomatic mode, someone does something, and the subsequent writings and rumors are treated as acts in response to that other deed, and we focus on studying the fallout and the implications around an alleged happening (how did the rumor of the one-eyed assassin function, what response did the alliance have to the alleged night raid, how do the competing heroic tales impact various audiences, etc.)

the approaches are of course not mutually exclusive, though certain orientations favor one over the other

how going back to the point about 'heroes' (and note that they don't have to mean outstanding individuals, this can also refer to peoples and collectives), even if portrayals about them are inaccurate and unreliable, it still remains the case that their deeds have made some impact and that the marks and traces cannot be completely erased... but the upshot is that whatever it is that they do it's not up to them how they will be interpreted

to give another example, consider for instance the bombing operations that happen in situations of armed conflict

one approach would be to investigate who did the dirty deeds and assess which reports are reliable

the other approach would be to investigate the impact on the landscape and the responses of survivors and descendants

both are ways of reckoning with what has happened, but emphasize different things

and even though Ravages spends much time problematizing the reliability of heroic tales and official records, it also attends to and recognizes the traces and markings that remain in spite of the distortions (or better yet, that the distortions themselves constitute traces and markings of responses to what may have happened)

on a meta note, the very project of Ravages is itself a response to the impact of 3K lore, the stories that captivated a guy in HK who worked on the advertising industry, enough to want to reinterpret the alleged events and reframe a bunch of characters and make money out of the effort along the way…

but before that, perhaps these two followup sentences (also from chapter 243, which also explores some of the things featured in 209-210) best summarize the ambivalence Ravages has towards both official accounts (such as the Records) and folk recollections (exemplified by the Romance)

historical records recounted the war in Xuzhou, but not the suffering behind it

folklore recounted the bravery of heroes, but not the truth behind it

the consolation (and the frustration) is that the truth of the matter is indirectly, obliquely, and misleadingly conveyed by its traces amidst the distortions

imagine seeing the tree rings on a stump of a tree trunk, but not knowing all the details of its life and death

ome things pierce through the obstacles and reach the descendants (us) - Guan Yu's sacredness, Lu Bu's prowess

it's not as simple as that though

story-wise, we see Huang Da being mentally marked upon witnessing Lu Bu's prowess, and we see Liu Bei being emotionally touched by Guan Yu's sense of honor (to the point that both boldly foreshadow how their legacies would live on)

but what remains with 'us' (and that includes Chen Mou as fellow enthusiast of 3K lore) are assorted retellings, attestations, testimonies with their own complex histories (not to mention the studies and debates about them), the veracity of which we are unable to completely ascertain (because as has been noted even in Ravages rumors and heroic tales can be garbled, records can be partial and partisan, etc.)

thus on the one hand we're not really sure about the truth of certain propositional claims and arguments (who really convinced Cao Cao to have Lu Bu executed, how many times have Lu Bu and Guan Yu really faced each other, etc.), but on the other hand it is nonetheless true that we have with us these relics and fragments regardless of the truth of their claims (and we can appreciate how they affect us and spawn their own spinoffs as 'continuations' of that lineage, plus we can speculate about the various factors that allowed certain rumors and tales to persist but not others)

take for instance the deification of Guan Yu

we're not sure how honorable he was (based on the accepted rubrics and criteria during late Han), and it's likely there are other 'honorable' people in that period but didn't end up becoming models for veneration, yet a confluence of factors may have helped push the name of Guan Yu to become an important cultural-religious icon today (in other words, 'Guan Yu' the symbol functions as a trace and effect of generations of meaning-making, once again reiterating the point that it's not up to 'heroes' of one time how they will be viewed by others, especially in subsequent generations and thus winners cannot completely shape the narratives to their liking)

suppose (since this is an in-universe thing) Lu Bu is as mighty as is claimed about him (and more) and that we as readers get privileged access for the sake of the argument